By Rev. Dr. Fritz Ritsch

April 7, 2019

John 12: 1-8

I became a Christian at age 14, and I like to tell people that I was a Teenage Evangelical, which is not too different from being a Teenage Werewolf. One of the things I remember, and often miss from that period of time was a strong sense that God was with me, and that Jesus was by my side. I prayed for hours and sought Jesus’ guidance on just about everything. I mean, everything. Etched in my memory is the time when I was in tenth grade that I saw a leather jacket that I really wanted in the store, but I was in an agony of uncertainty as I tried to figure out whether it was God’s will that I should buy it. Oh my gosh, I’d look so good in it! But isn’t that pride? It’s costs $35 in 1975 dollars! That’s a lot of money! Is that really the way God wants me to spend it? I remember the agony of uncertainty so distinctly that I actually can’t tell you whether I bought the jacket or not!

But I often think about that. At one level, it seems over the top. Was I really that convinced God cared whether I bought a jacket or not? But at another level, it represents the fact that even when I felt so certain Jesus was near to me, it didn’t make discerning God’s will any clearer. I never had that sense that apparently other people have that “God is pointing me in that direction, I should go there.”

But what I normally have found is that God doesn’t give us unambiguous guidance in life, and being Christian doesn’t guarantee clarity and order in life, no matter what some people tell us. At the same time I was figuring out whether God wanted me to buy that jacket, I was dealing with my mom’s mental illness and occasional suicidal behavior. I wanted answers. I wanted certainty. I wanted the clarity other Christians talked about, like the ones on the 700 Club, about being certain exactly what God wanted me to do in every difficult situation. For those people it seemed like their faith made their lives were a simple math problem to solve—you only needed to plug in a couple of variables and viola, you’d get the answer. To me life was more like a poem whose meaning I’m trying to discern. It was beautiful but it was also tremendous, awe-full in the original meaning—filled with awe and wonder but also overwhelming and terrifying, full of multiple meanings, disturbing to your soul, and often ambiguous in meaning.

Ambiguity also seems to dog our Gospel lesson today, the story of Mary of Bethany anointing Jesus’ feet. Commentators focus on comparing the story to similar stories in the other gospels, pointing out the main differences, but otherwise they leave it quickly. Much more interesting to them, and to all of us, I suppose, are the stories that frame it. After Mary washes Jesus’ feet is the Triumphal Entry, when Jesus rides into Jerusalem and is proclaimed king. A few days later, he will be executed.

Before Mary washes Jesus’ feet, there is the story of her brother Lazarus, who was dead but who Jesus miraculously raised from the dead. This becomes the catalyst for the Judean religious council, the Sanhedrin, to decide to try to kill Jesus.

It’s an example of the way that people of faith can be absolutely certain they are right, but they are wrong. You and I look at Jesus raising Lazarus from the dead and think, “How could it be more obvious that Jesus was sent by God and that the religious leaders should listen to him?”

But the religious leaders seem to view in exactly the opposite way. The Jerusalem leadership gathers in a private meeting and express frank, unambiguous terror about Jesus’ miracles and signs. They are fearful that the people will proclaim Jesus king and it will lead to a rebellion that the Romans will then quash brutally and violently.

Then Caiaphas, the high priest, shuts down all the kvetching and nail biting. “You know nothing at all!” he proclaims. “You do not understand that it is better for you to have one man die for the people than to have the whole nation destroyed.”

The Bible continues that “He did not say this on his own but being high priest that year he prophesied that Jesus was about to die for the nation, and not for the nation only, but to gather into one the dispersed children of God. So from that day on they planned to put him to death.”

Why do the religious leaders find the resurrection terrifying instead of hopeful? We often joke that there are only two things certain—death and taxes. But the truth is only one of those two things is really certain: death. The certainty of death, for better and for worse, is what organizes our lives, and keeping order is what keeps the powerful in power.

But the promise of resurrection upends that order because death is no longer certain. It creates uncertainty; it disrupts the natural order of things. It is wonderful and terrifying. Anyone who believes in order and certainty, anyone who is invested in it as religious and political leaders are, will be terrified of the ambiguity and complexity that the possibility of resurrection brings. The priests and Pontius Pilates of the world will want to stifle it—they will want to kill resurrection.

But the story is different for Lazarus’ sisters. Mary and her sister Martha had been devastated when their brother Lazarus had died, but they were even more devastated when Jesus arrived to Lazarus’ bedside too late—four days too late. Martha comes out to confront Jesus, saying, “If you’d been here, my brother would not have died.”

Mary, however, is so grief-stricken, and apparently so angry and hurt, that she at first refuses to come out even to meet Jesus. When she does, she says the same thing that her sister Mary said: “If you’d been here my brother would not have died.” But somehow it twists the knife for Jesus in a way that Martha’s complaint does not. The scriptures say that after Mary spoke, “Jesus was deeply disturbed in spirit and greatly moved.” Following this Jesus goes to Lazarus’ grave and scriptures tell us, “Jesus wept.”

And then he raised Lazarus from the dead.

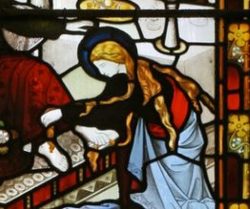

In our Gospel lesson today it is a few days later, and Mary and Martha are hosting a dinner party in Jesus’ honor, and their resurrected brother Lazarus is at the table with them. Then Mary does this bizarre ritual—she drops to Jesus’ feet, covers his feet with enormously expensive perfume, and then dries his feet with her hair—an extremely vulnerable and intimate act.

Jesus immediately connects it to his death. This is enbalming perfume, he says. Perfuming the feet is one of the rituals that ancient Jewish society engaged in when embalming their loved ones. Mary predicting Jesus’ death. And this is important. The high priest Caiaphas was an unintentional prophet, but Mary here is an intentional one. She is saying, she knows Jesus will die.

Mary of Bethany is a prophet. But her prophesy is not yet done.

Because death has a completely new meaning for her now that her brother Lazarus has been raised from the dead. Before and during her brother’s death, death may have been terrible, but it was unambiguous. It was final. It was permanent. It was the end.

But now that Lazarus has risen, death is no longer unambiguous. Death has become the doorway to the resurrection. Now Mary believes; now Mary has total and complete faith in Jesus. But with faith comes not certainty, but ambiguity. That ambiguity is what creates the emotional tension that so characterizes this scene in our Gospel reading. Mary is grateful but she is also afraid. She is rejoicing, but she’s also grieving. She is prophesying that Jesus will rise from the dead, that death will not have the last word.

But that promise of resurrection is not an uncomplicated promise. The miraculous hand of God has invaded the Newtonian orderliness of the world in which we live. It makes the one thing that is certain–death–completely uncertain. That in turn makes life uncertain. It reminds us that all our attempts at control are pointless. All that is rests in the hands of sovereign God and it is this God who truly controls our lives and all of history. It is the sovereignty of God that the resurrection has taught Mary, and that is what gives this simple story its complex emotional power.

In the face of God’s sovereignty and the power of resurrection to upset the order of things, Mary is emotionally conflicted: grateful and fearful, desirous and afraid, faithful and uncertain, grieving and joyous. So what does she do is this conflicted state?

She serves.

And in doing so she is once again a prophet, because she predicts something that happens five days later, when Jesus is with his disciples at the last meal before his arrest.

Jesus strips down to his skivvies—another humble, intimate act, like Mary letting down her hair—goes down to his knees and washes his disciples’ feet, using the towel, which is his only clothing, to dry them. Jesus’ disciple Peter is indignant. “Lord, why do you wash my feet?” Jesus replies, “You do not know what I am doing, but later you will understand.”

But guess what—what Peter, the gang boss of the disciples doesn’t understand, The Prophet Mary of Bethany had completely understood five days earlier, when she fell to her knees to wash Jesus’ feet. Jesus tells his disciples that he has washed their feet because “If I, your lord and teacher, wash your feet, then you certainly ought to wash one another’s feet.” In other words, everything that Jesus teaches—everything that his life stands for—everything that God expects of us—is that we must be servants. That is the core of everything you need to know about Jesus and everything you need to know about God and everything you need to know about being Christian. Jesus dies and rises again to serve God and also to serve humankind, for the sake of all of us. He serves and calls us to serve.

And the Prophet Mary of Bethany predicted that very message by washing Jesus’ feet five days before Jesus washes his disciple’s feet. Maybe even her act influenced Jesus. Maybe he’d been thinking, “Hm, how in the world am I going to get it through my disciples’ thick heads that everything I’m about is service?” and then Mary washed Jesus’ feet and he thought, “Ah ha! That’s how!”

The Prophet Mary of Bethany is the first of Jesus’ disciples to understand the full, complex and unsettling truth of who Jesus is and of what the resurrection means. Resurrection turns the whole world on its head. Certainty is uncertainty, darkness is light, chaos is order, grief is joy, despair is hope—because death is resurrection. The natural order has been replaced by a complex, unnatural, miraculous order.

In the world of order, leaders like the high priest and Pontius Pilate and King Herod and Caesar like to have their hands on the reins—they like to be in control, and they know they can be. But in the world of the resurrection none of us is in control. None of us can be certain. The whole world order rests in the hands of God. None of us can assume we know how things will turn out now, except to say that somehow, by the grace of God, it will all turn into resurrection—a new us, a new you, a new me, a new world, held in the hand of a loving all-powerful God. That is good news, but it sure creates a lot of ambiguity and uncertainty and discomfort.

In a world that seems orderly, the way to get on top is to be in control. An orderly world calls for high priests and caesars and kings and queens and presidents. It calls for people to make sure that order is maintained.

But in a world where the certain is uncertain, where order is turned upside down by a sovereign miracle performed by a sovereign God, the proper response isn’t to be in control—the proper response is to serve. The proper response is to love. The proper response is to bow in awe before God, and to bow in service to your fellow human beings.

In the early sixteen hundreds, London was hit by the disease already scourging the rest of Europe, the bubonic plague. In those dark, pre-science days, both the causes and the cures for disease were shrouded in mystery. But that didn’t stop preachers, government officials, and theologians from spouting their absolute certainties that the causes of the plague were entirely theological—that this was a disease brought on somehow by the sinfulness of the people who acquired it. As the powerful and the privileged are wont to do, they tried to cast this disease as part of an understandable moral natural order.

Once these privileged individuals determined the plague was a curse from God, the next logical step was get out of town. Such was the behavior of a cleric who was already on the path to becoming one of the most prominent clergymen of his age, Lancelote Andrews, who abandoned his plague-infested parish of Chiswick to flee to the country. “’The razor is hired for us,’ he told his congregation, ‘that sweeps away a great number of haires at once.’ Plague was a sign of God’s wrath provoked by men’s ‘owne inventions,’ the taste for novelty, for specious newness, which was so widespread in the world.’” In other words, Andrewes maintained before he packed his bags and fled to the country, the plaque was caused by people upsetting the proper order of things by seeking the new, the surprising, the different.

In contrast to this behavior, says Adam Nicholson in God’s Secretaries,

was the example of the near-saintly Thomas Morton, … the rector of Long Marston outside York, later a distinguished bishop, who, in the first flush of this plague epidemic as it attacked York in the summer of 1602, had sent all his servants away, to save their lives, and attended himself to the sick and dying in the city pesthouse. Morton slept on a straw bed with the victims, rose at four every morning, was never in bed before ten at night, and travelled to and from the countryside, bringing in the food for the dying on the crupper of his saddle.[1]

In the midst of confusion, ambiguity, terror and disorder, Thomas Morton knew what he had to do. He knew that he wasn’t to run in fear, or to explain away all these things by pretending to know answers he didn’t know. He chose instead to serve, to love, to risk all in chaos. He didn’t need to explain away suffering, but only to do what Jesus has always commanded us to do in the midst of ambiguity, uncertainty, and disorder—to serve. Instead of being terrified by the power of death, he was inspired by the power of resurrection. He chose simply to serve.

In so doing, he took Jesus’ path, and followed the inspired example of the Prophet Mary of Bethany.

[1] Quotes from Nicholson, Adam, God’s Secretaries: The Making of the King James Bible. HarperCollins e-books, Chapter Two, “The Multitudes of People Covered the Beautie of the Fields.”